Dodgy radiocarbon modelling at Tell el-Hammam (not-Sodom)

A recent paper in the Nature Group’s Scientific Reports claimed that Tell el-Hammam, a prehistoric site in Jordan, was destroyed by a “Tunguska-sized airburst” around 1650 BCE – strongly implying it is therefore the site of the biblical Sodom. The paper has been roundly debunked on social media, most notably by impact physicist Mark Boslough, who has exposed the murky backgrounds of the authors. I can add that the radiocarbon modelling is also completely incoherent.

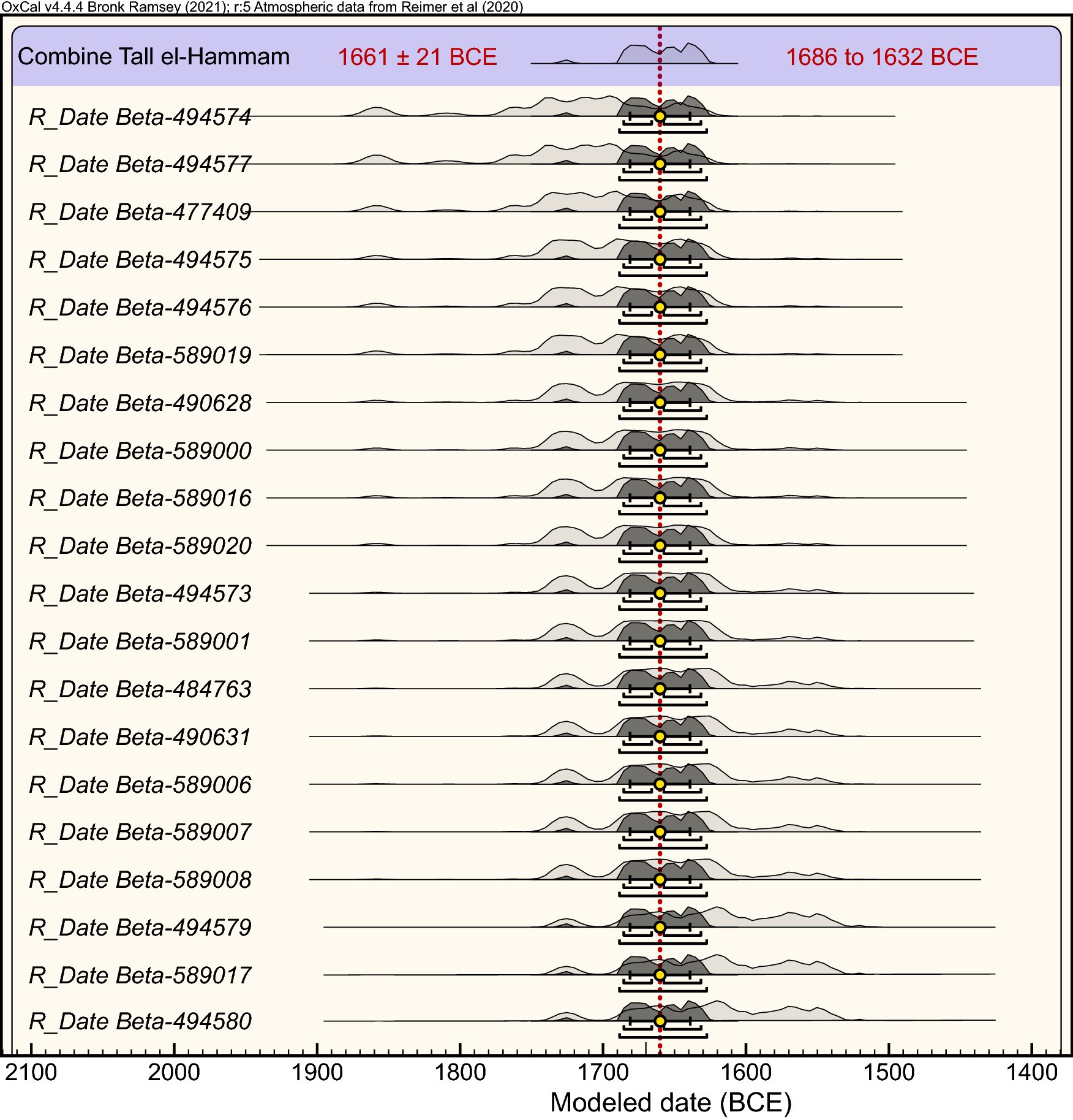

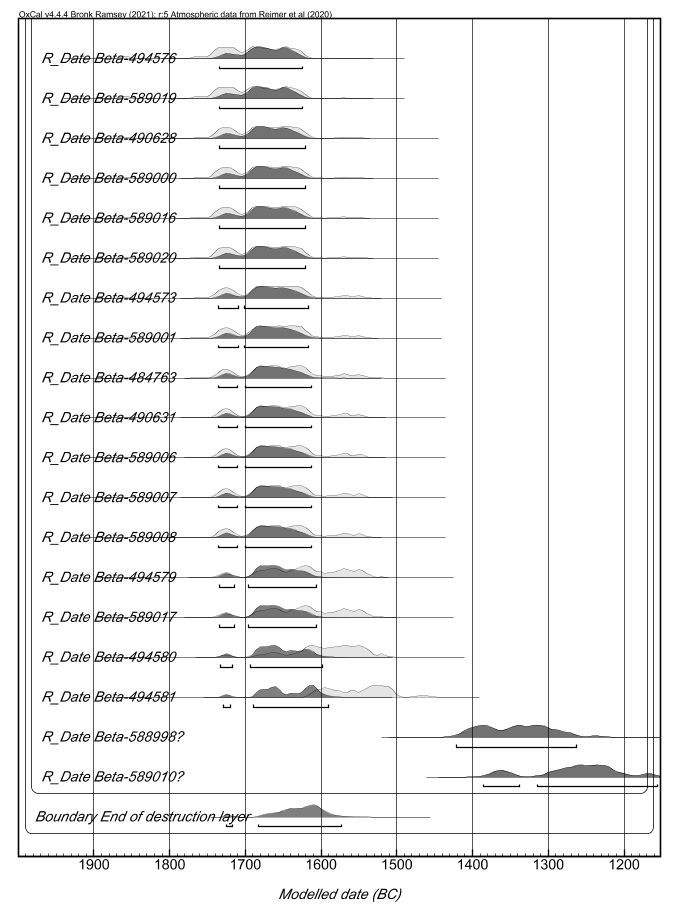

The authors say they used OxCal’s “Combine routine that statistically tests the hypothesis that multiple radiocarbon dates relate to the same event” which “determined that 20 of 26 14C dates are statistically synchronous and likely represent a single event”. In fact, ‘Combine’ is used to combine (see the OxCal manual; but the clue is in the name) dates that you already know represent a single event. In other words it says, if we assume all these radiocarbon dates are really the same date, what’s the best estimate of what that date is? It doesn’t “test” anything because, big surprise: if you build a model with the assumption that all these things happened at the same time, that model is going to tell you that they all happened at the same time. You only have to eyeball the un-modelled dates (the light grey curves in the background of their figure below) to see that the dates from their “destruction layer” could actually have taken anything up to 300 years to accumulate.

So their ‘model’ of the radiocarbon dates actually just regurgitated their assumption that all their dates related to the same catastrophic event. But it’s not hard to model this data properly. We can just run the dates with a more reasonable set of assumptions: that the radiocarbon samples are related to each other (because they were found in the same archaeological layer), but that we don’t know a priori how long that (1.5 m-thick!) layer took to form.

With this model, the so-called “burn layer” dates to somewhere between 1770 and 1575 BCE. OxCal also tells us that it could have taken anywhere up to 155 years to accumulate (with 95% probability). You could probably narrow it down a bit further with dates from layers above and below the event of interest, but, as the authors note and then ignore, radiocarbon dating has its limitations and will never be precise to more than a few decades.

This matters because the signs of high-temperature burning they point to can also be produced by infrequent but normal events like lightning strikes or furnace fires. If you are analysing 150 years of accumulated sediment, it is obviously much more likely you will find these. Similarly the evidence for the ‘destruction’ of the site, like the fragments of bone scattered around (which as Chris Stantis explains is already not that much for a tell site), looks even more like normal debris and decay if it built up slowly.

I’m not qualified to judge the geophysical evidence for an impact (Boslough is, and doesn’t think much of it). Even if the geophysical evidence is there, it rests on the assumption that all the samples they looked at came from the same event but based on the radiocarbon and archaeological evidence in the paper, the so-called “destruction layer” or “burn layer” just looks like the kind of slow collapse of buildings and accumulation of trash that happens whenever a site (or part of a site) is abandoned for a while.

Adapted from the original Twitter threads (1, 2) on 2023-04-13.