What did the first farmers actually farm?

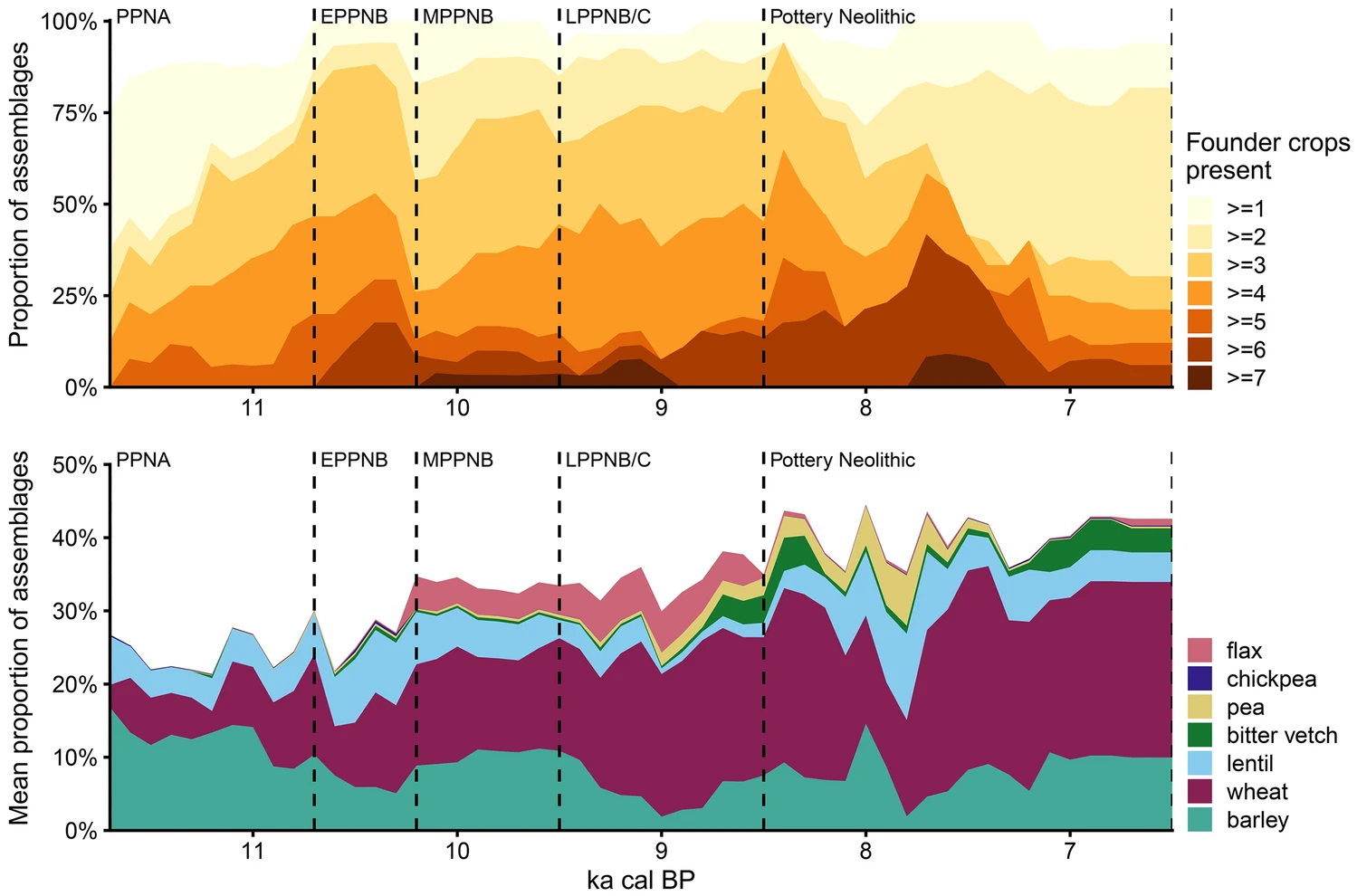

Eight so-called founder crops—emmer wheat, einkorn wheat, barley, lentil, pea, chickpea, bitter vetch, and flax—have long been thought to have been the bedrock of Neolithic economies. But early prehistoric sites in Southwest Asia keep turning up more ‘exotic’ (to us) species, like the sedge tubers mixed into the earliest known breads or the new glume wheat, an important ancient crop that’s now extinct.

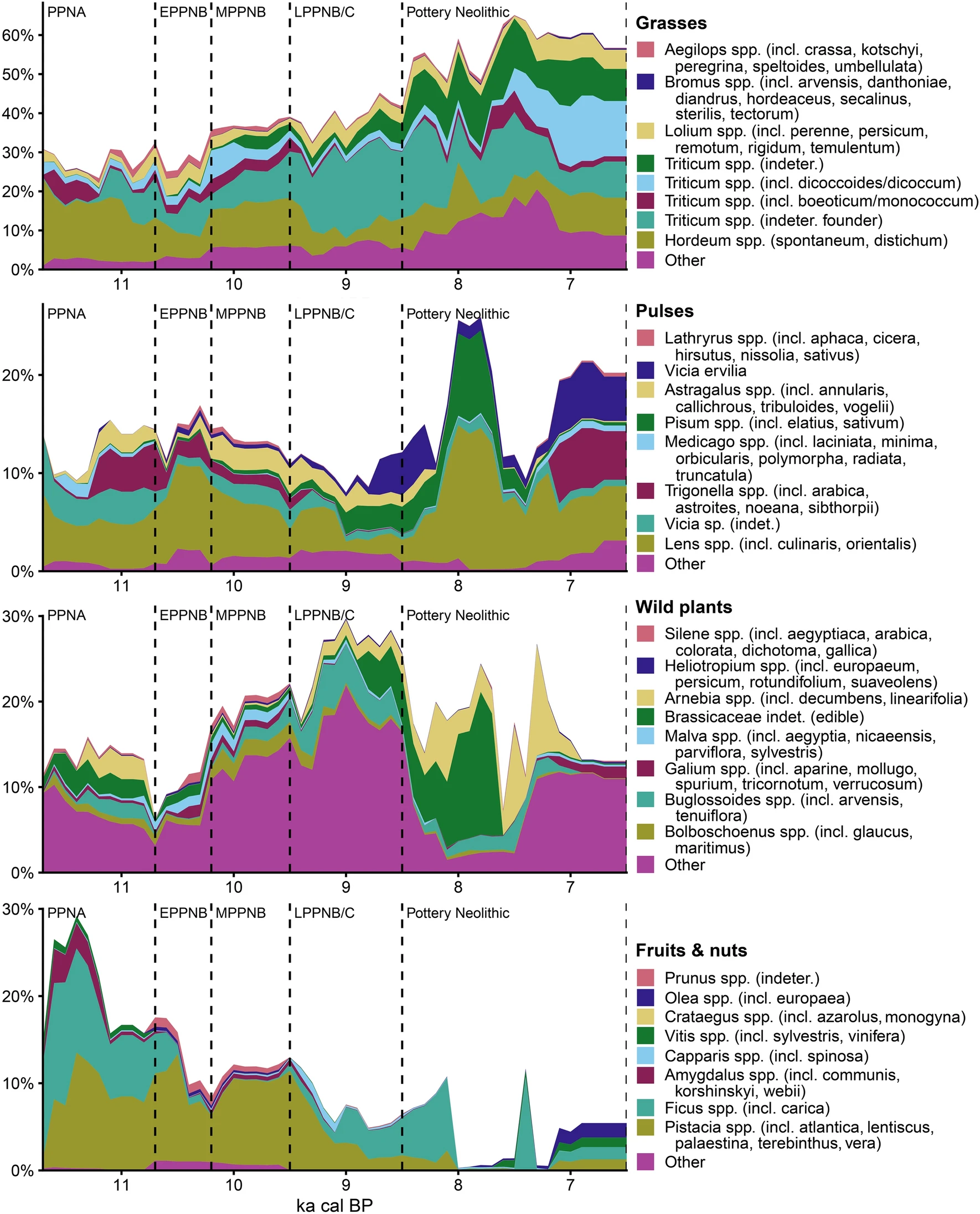

Is it a coincidence that the founder crops are all species that remains staples today? In our new paper, Amaia Arranz-Otaegui and I examine what plants actually turn up the most in the remains of the earliest agricultural societies. We gathered data on 144 million botanical remains from 135 prehistoric sites across Southwest Asia. Our analysis included the Neolithic (c. 9700 to 4500 BCE) and the periods immediately before and after – 10,000 years of plant exploitation. We found that Neolithic economies were much more diverse than previously thought, incorporating dozens of species of cereals, legumes, small-seeded grasses, brassicas, pseudocereals, sedges, flowering plants, trees, and shrubs. Free-threshing wheat, grass pea, faba bean, and ‘new’ glume wheat were especially widely cultivated.

It turns out that the ‘founder crops’ weren’t particularly special at all: rarely cultivated for the first thousand years of the Neolithic, they were never ubiquitous, weren’t the first species to be domesticated, or the first or only to be spread outside of Southwest Asia. They did become more common over the course of the Neolithic but, remarkably, this can be explained almost entirely by a steadily increasing reliance on wheat as a staple crop. There’s a story waiting to be told there, I’m sure! For us, it no longer makes sense to talk about crop packages. Neolithic farmers cultivated, managed and otherwise experimented with a huge diversity of plants. Tracing the individual trajectories of these crops in the accumulated archaeobotanical remains reveals many fascinating new stories.

For more details, see our new open access paper in Vegetation History & Archaeobotany. The data and R code supporting the analysis is available on GitHub and Zenodo.