Computational archaeology, digital archaeology, and associated ologies

Archaeologists like to define themselves by their material. Asked “what do you work on?” at a conference, their response will most likely be something like zooarchaeology, archaeobotany or “pottery”. We all also have a range of other, cross-cutting interests in certain regions, periods, theories and topics – but it’s what we look at that largely determines our day-to-day existence.

For a while now, I’ve been calling myself a computational archaeologist. I think this neatly captures what it is I look at: data, figures, and above all, computer code. It also sounds a lot more put together than the ad hoc labels I used to get: “modeller”, “GIS person”, or “I don’t know, what are you doing over there?” I’m following the lead of my alma mater the Institute of Archaeology, which some years ago started a master’s course in computational archaeology, as well as fellow comparchs like Isaac Ullah and Stefani Crabtree.

Still, computational archaeology is a relative neologism, and most of the time people don’t really know what I’m taking about. There is also a cloud of more-or-less related terms—digital archaeology, digital humanities, archaeoinformatics, data science, and so on—many of which have wider currency but which I don’t think capture quite the same thing.

So what is computational archaeology? What distinguishes it from its cousins? Where does it fit in the grand heirarchy of archaeo and other ologies?

What is computational archaeology?

In short, computational archaeology is using computers to understand the human past. There is a subtle but important distinction between this and using computers to do archaeology. All archaeologists use computers extensively. Many specialise specifically in the application of digital technologies to the discipline – this is digital archaeology, but more on that below. Computational archaeology has a more restricted domain.

As Isaac Ullah has argued, we ought to see the root of computational archaeology in the word computation more than computer. It is analogous to the better-established “computational” wings of other branches of science: computational biology, computational economics, etc. That is, what is important is not the tool, but what the tool was built to do: run programs that make computations. All archaeologists use computer programs as tools. But crucially, for computational archaeologists, computer programs are also our material. We study computer programs in the way that zooarchaeologists study animal bones or archaeobotanists study plants – not as objects in themselves (as a computer scientist would), but as a means for making inferences about the human past.

How can computer programs, a thoroughly modern artefact, be material for archaeological study? Unless you are doing software archaeology1 – not directly. Computational archaeologists need something that mediates their material (computer programs) and the phenomena they want to make inferences about (the past). This is where comparch’s strong association with statistics (mediation through data) and formal modelling (mediation through theory) enters the picture. It is also a point of divergence. To borrow Ullah’s terminology, analytic computational archaeology makes inductive inferences from data, whilst generative computational archaeology makes deductive inferences from simulation. They differ markedly in theory and in practice. What unites these sub-branches2 is the use of computation as the primary material for understanding the human past.

This definition still leaves room for a diverse set of scientific practices. A computational archaeologist could be doing straightforward descriptive statistics, classical hypothesis testing, Bayesian inference, or any number of other species of modelling; they could be using complexity science, network science, complex adaptive systems theory, cultural evolution theory, and so on; their data can be anything old or new that archaeologists can count, measure or classify – or none at all. Like archaeobotanists or pottery specialists, computational archaeologists aren’t defined by the questions we are trying to answer or even the methods we use, but by our material.

Digital archaeology and computational archaeology

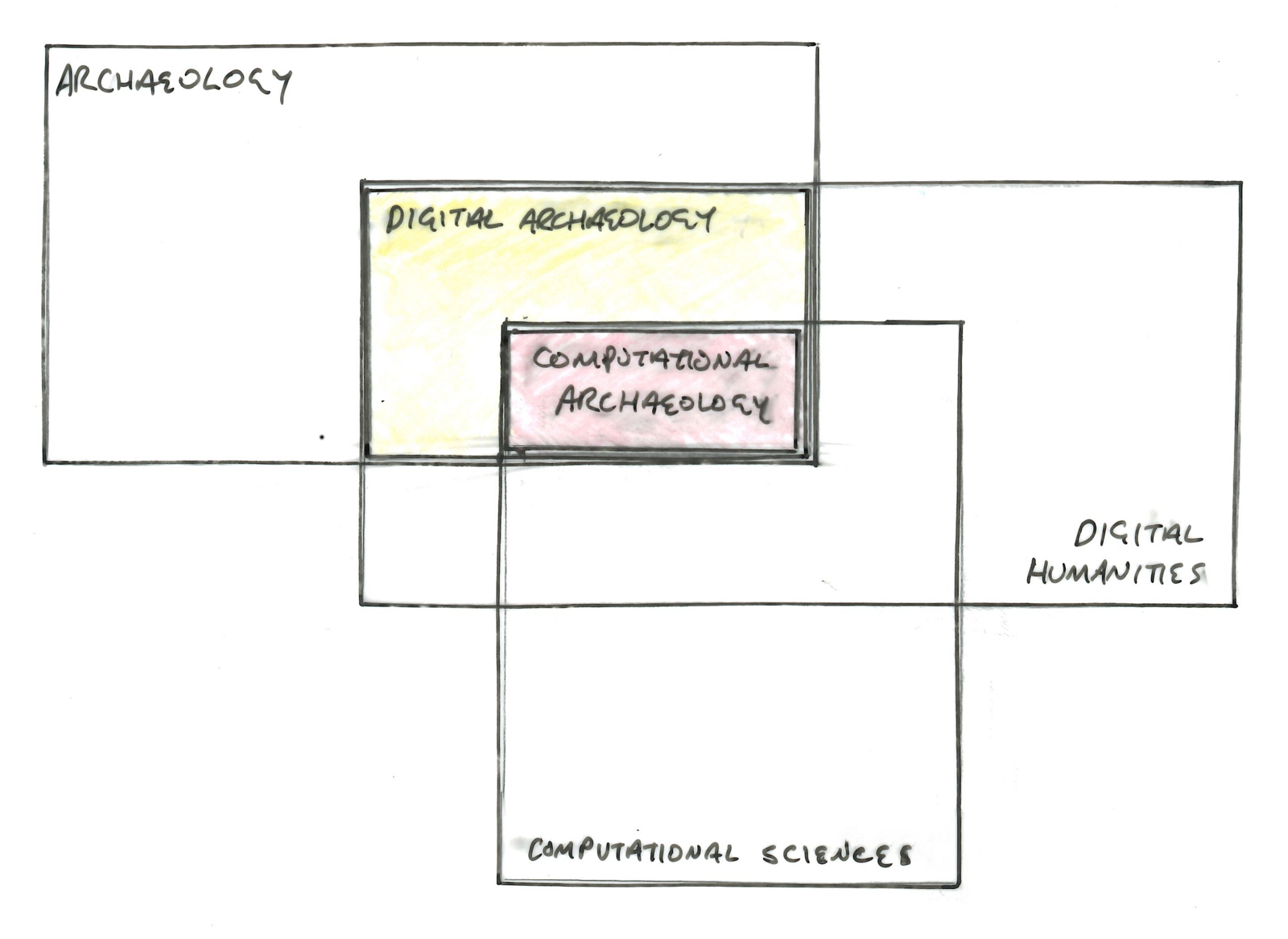

Digital archaeology is a broader church. It can accommodate any application of digital technology to archaeology: digital photography, 3D scanning and photogrammetry, remote sensing, field recording, information systems, publishing, critical engagement, sensory studies, and doubtless several more fields that have been invented by the time you read this. Computational archaeology is just one subset of digital archaeology; computational archaeology is to digital archaeology as zooarchaeology and archaeobotany is to environmental archaeology.

We can see digital archaeology as the broad manifestation of digital humanities research in archaeology. Computational archaeology, meanwhile, occupies the specific intersection between the digital, the computational and archaeology.

Does it make sense to delineate computational archaeology as a distinct branch of digital archaeology? I would argue that it is more than an arbitrary carving out of territory. Digital archaeologists can use computerised tools to further archaeological understanding through any number of conventional or innovative intellectual frameworks. Computational archaeologists focus narrowly on computation as a basis for inference. But it is difficult to argue against the proposition all computational archaeologists are digital archaeologists, unless you can find somebody still working purely with pen and paper or an analog calculator.3 We are archaeologists whose research is inseparable from digital technology, after all.

Archaeoinformatics, data science, and archaeostatistics

There remain a few ‘rival’ terminologies to computational archaeology, which I’ve no reason to not use other than semantics and personal preference.

Archaeoinformatics is a term that doesn’t have much currency in the English-speaking world, but it is more common in mainland Europe. The University of Cologne has a master’s programme in archaeoinformatics and calls it a synonym of computational archaeology. If I were to indulge my splitter urges, I’d reserve it for the development and study of archaeological information systems – by analogy with geoinformatics and GIS. But I must concede that it is rarely (if ever) used that way.

Data science is very trendy. Defined as the interdisciplinary application of mathematics, visualisation and computer programming to learn from data, it sounds very much like what computational archaeologists bring to archaeology (at least analytic computational archaeology). Personally, I’m sympathetic to the view that it is just a rebranding of statistics – a buzzword that appeals to the commercial world, and those don’t tend to have long lives! It is also not the most compoundable phrase: are we doing archaeodata science? Data archaeology? (Isn’t that all archaeology?)

Archaeostatistics is an older term which sadly never seems to have caught on. I’d tend to see it as a synonym of computational archaeology, made somewhat obsolete by the fact that statistics is rarely done without a computer these days; a handy shorthand for analytic computational archaeology, perhaps.

-

Recent research in archaeogaming, for example. ↩

-

Or sub-sub-sub-branches? ↩

-

Could you still call them a computational archaeologist? I’d argue yes – they are just using themselves as the computer, in the original sense of the word ↩