Little Red Riding Hood and the Second Wave Phylomemeticists

Jamie Tehrani has a very imaginative paper in PLOS ONE on The Phylogenetics of Little Red Riding Hood:

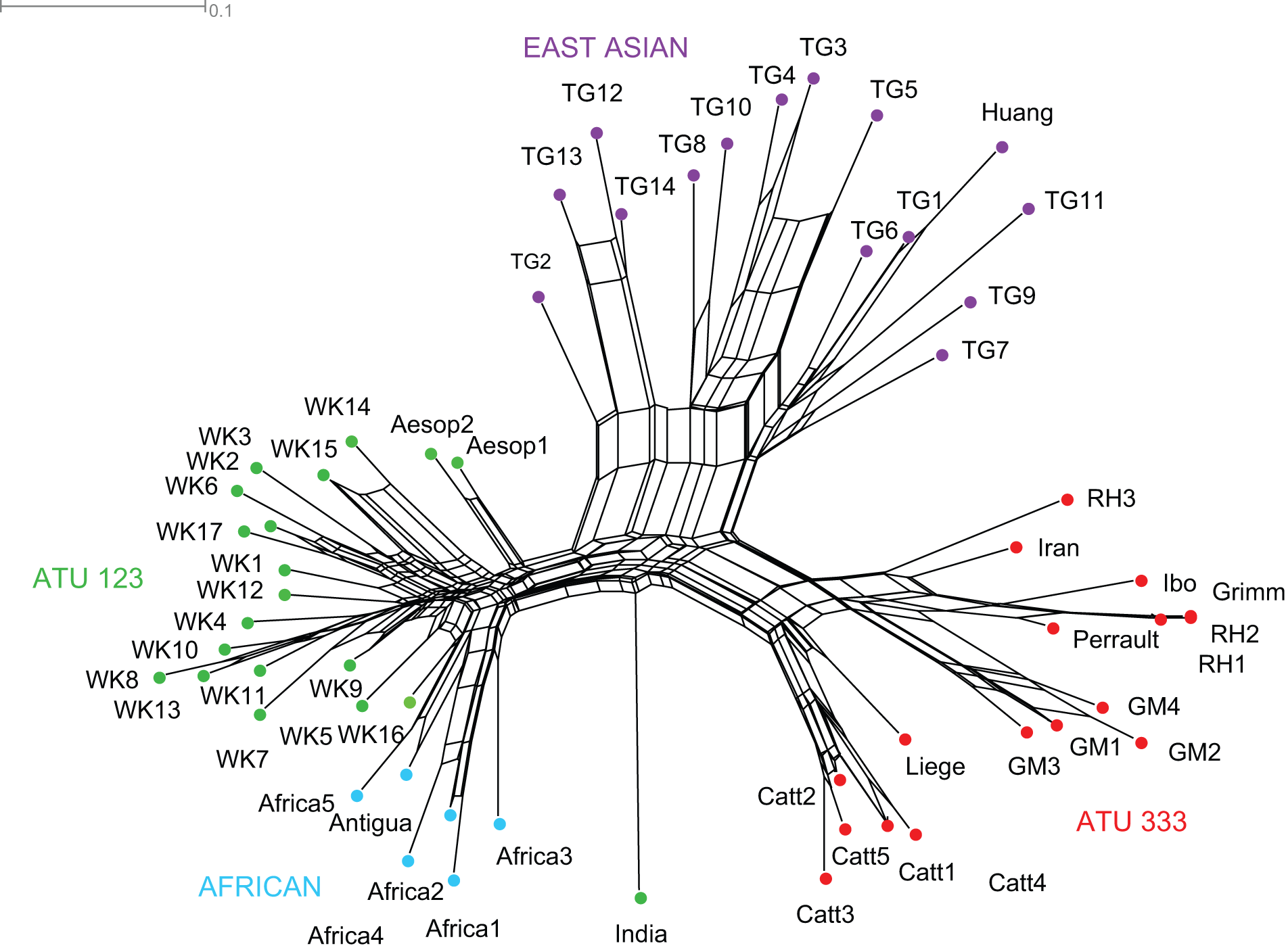

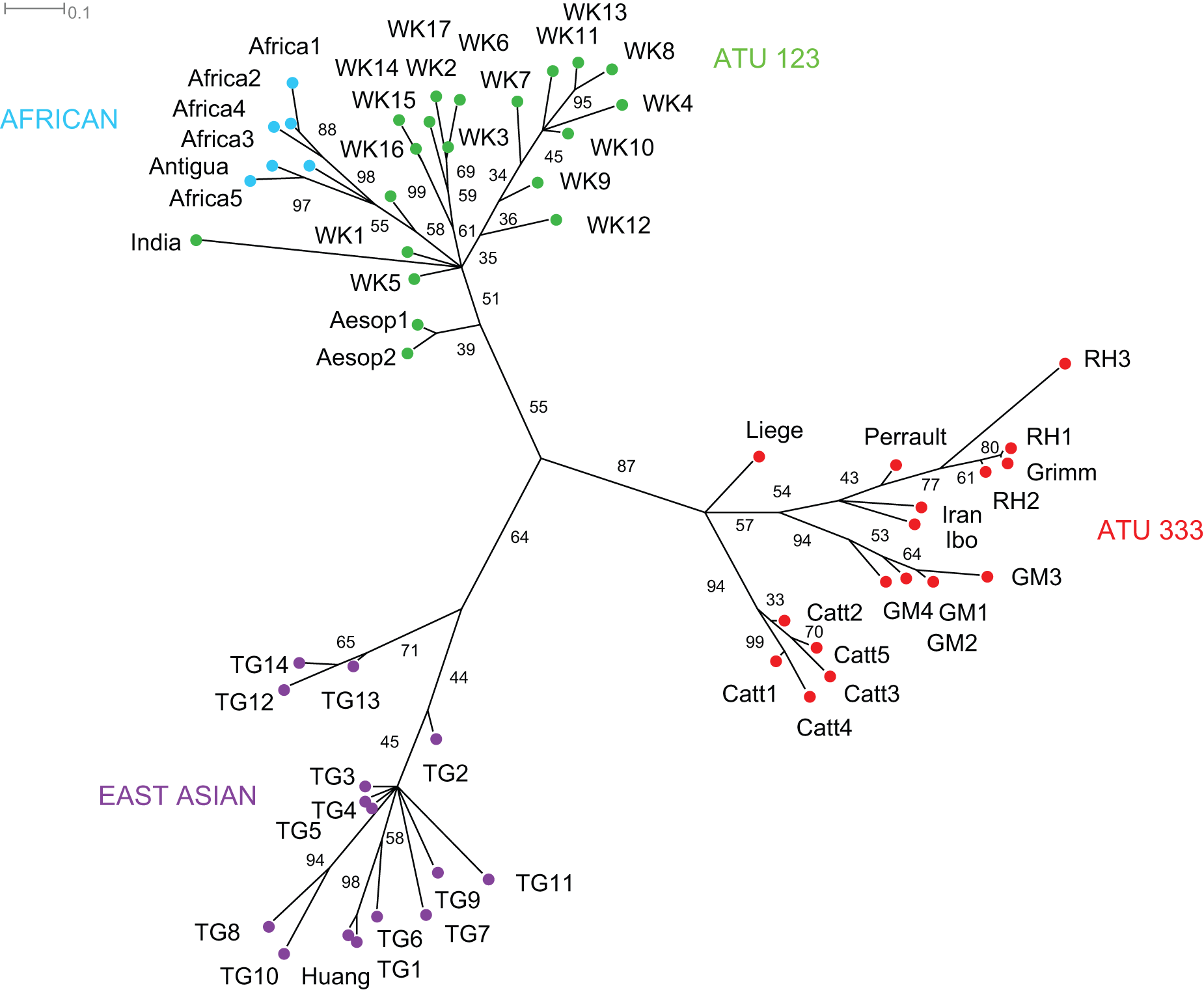

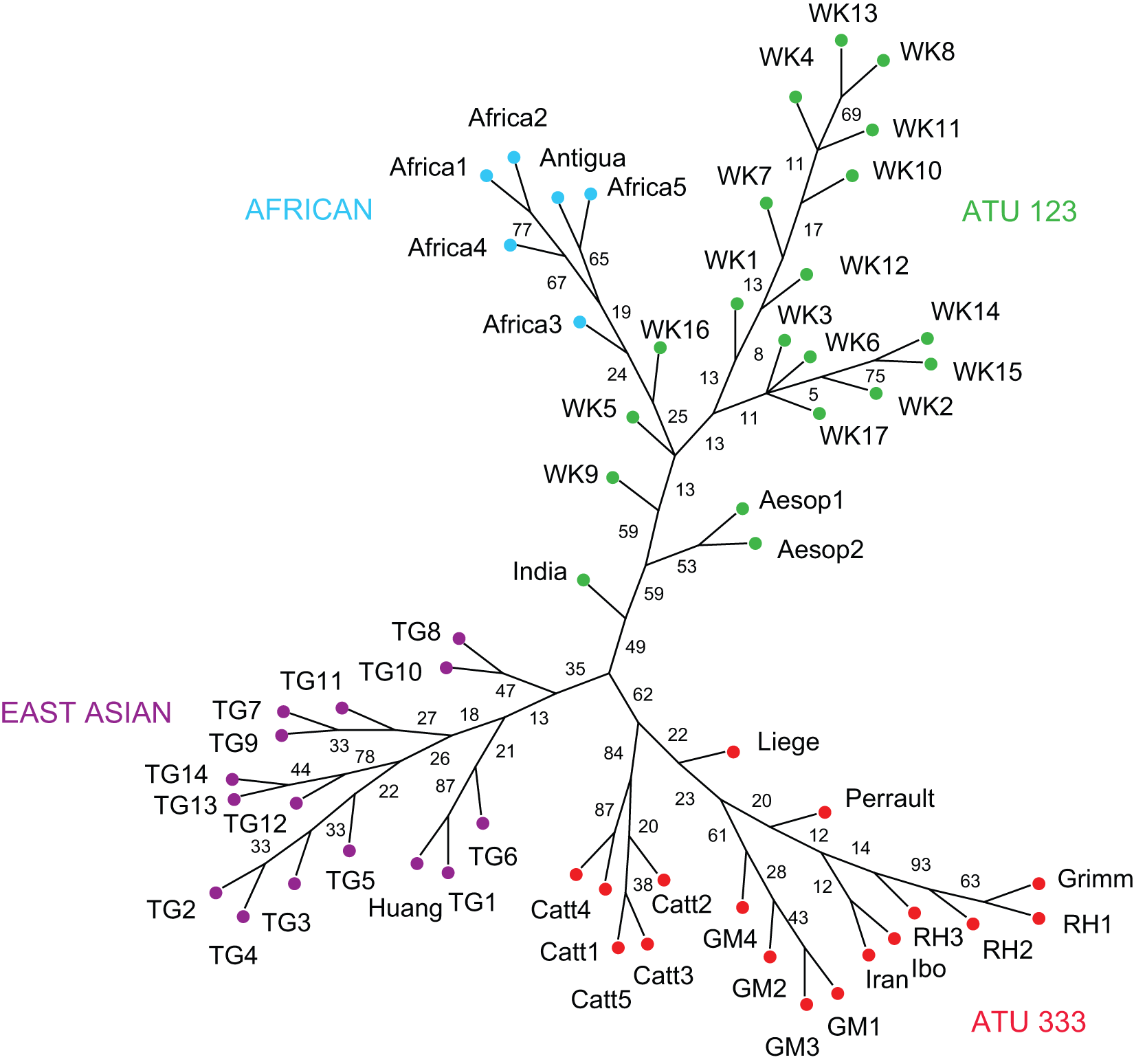

Researchers have long been fascinated by the strong continuities evident in the oral traditions associated with different cultures. According to the ‘historic-geographic’ school, it is possible to classify similar tales into “international types” and trace them back to their original archetypes. However, critics argue that folktale traditions are fundamentally fluid, and that most international types are artificial constructs. Here, these issues are addressed using phylogenetic methods that were originally developed to reconstruct evolutionary relationships among biological species, and which have been recently applied to a range of cultural phenomena. The study focuses on one of the most debated international types in the literature: ATU 333, ‘Little Red Riding Hood’. A number of variants of ATU 333 have been recorded in European oral traditions, and it has been suggested that the group may include tales from other regions, including Africa and East Asia. However, in many of these cases, it is difficult to differentiate ATU 333 from another widespread international folktale, ATU 123, ‘The Wolf and the Kids’. To shed more light on these relationships, data on 58 folktales were analysed using cladistic, Bayesian and phylogenetic network-based methods. The results demonstrate that, contrary to the claims made by critics of the historic-geographic approach, it is possible to identify ATU 333 and ATU 123 as distinct international types. They further suggest that most of the African tales can be classified as variants of ATU 123, while the East Asian tales probably evolved by blending together elements of both ATU 333 and ATU 123. These findings demonstrate that phylogenetic methods provide a powerful set of tools for testing hypotheses about cross-cultural relationships among folktales, and point towards exciting new directions for research into the transmission and evolution of oral narratives.

The idea isn’t new. It’s been over a decade since it was first demonstrated that it’s possible to construct a phylogeny of material culture. Since then, phylomemetics has been applied to a dizzying array of archaeological, linguistic, textual and ethnographic datasets – it is easily the most well-developed methodology to come out of cultural evolution theory to date. But a lot of the early research read like proof of concepts. First wave phylomemeticists used esoteric data sets (for example early modern European cutlery), chosen for availability not relevance, and focused firmly on methodology: establishing that you can apply phylogenetics to cultural data, exploring new and exciting variants of cladistic analysis (maximum parsimony, Bayesian, network, cophylogeny, and so on) and convincing themselves that the results were meaningful. They rarely reached conclusions far beyond “this works.”

A lot of this was necessary groundwork, but now we can be confident that yes, culture evolves and diversifies, and yes, we can use phylogenetic analysis to trace it. Tehrani’s paper exemplifies the second wave of phylomemetics. He addresses an established problem that traditional approaches to the study of culture have not been able to solve. He concisely establishes that his phylogenies are consistent and well-supported rather than dwelling on the methodology and its theoretical justifications. And he interprets his results in context, drawing a novel conclusion about the cultural history of his data. This is the kind of research that is needed if cultural evolution theory is going to prove its potential to integrate the study of human culture in a Darwinian framework.

Bibliography

- Jamshid J. Tehrani (2013). The Phylogenetics of Little Red Riding Hood. PLOS ONE doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0078871