Open archaeology: a survey of collaborative software engineering in archaeological research

Zack Batist and Joe Roe

Paper presented at Computer Applications & Quantitative Methods in Archaeology (CAA), Limassol (Virtual), 2021.

Abstract

Archaeologists increasingly rely on specialised digital tools and computer code to conduct their research. Scientific programming languages such as R and Python are used to write, modify, comment on, review, share and reuse scripted analyses, enabling more advanced manipulation of digital data [@Schmidt2020]. This usually consists of custom scripts and project files that parse and transform archaeological data using generic functions for data manipulation, statistical analysis, and visualization. These are drawn from a range of ‘off-the-shelf’ packages, such as: the tidyverse, ROpenSci, or NumPy data analysis ecosystems; database management systems and visualisation engines; or modelling frameworks and specialised software from other disciplines and industries. Collectively, these tools support a broad set of applications common across research settings. However, as archaeological workflows are rarely explicitly accounted for in their design, they can also impose limits and force archaeologists to adapt tools in ways unanticipated by their developers.

As digital methods have become increasingly central to archaeological research, it is therefore becoming more common for archaeologists to develop software explicitly targeted at their use cases. These tools fundamentally differ from analysis scripts in that they are designed for reuse by multiple analysts for multiple applications within a given problem domain. They provide generic functions that can handle mutable inputs, rather than custom procedures tailored to a specific dataset and analysis, based on the designers’ assumptions about what data structures, processes and desire outputs are shared by the tool’s intended users. As such, building these tools evokes a distinct set of skills, shifting the developer from the role of analyst to that of a ‘research software engineer’ [@Baxter2012]. Although the intersection of archaeology and software engineering is not new, these contemporary projects are distinguished by their adoption of practices from open source software development. In particular, widespread use of the git version control system, associated web-based source code management platforms such as GitHub and GitLab, is a relatively recent trend, opening up a new set of workflows for collaboration between multiple developers.

In this paper, we survey the state of the art in archaeological software engineering, documenting the wide range of general-purpose digital tools currently in development. Using open-archaeo (https://open-archaeo.info/), a curated list of 300+ active open source archaeological software packages, augmented with data collected from GitHub’s API, we seek to identify emerging norms in software development and collaboration, focusing on three key questions:

- What types of open source projects are have been developed by archaeologists over the last 5–10 years?

- To what extent to these projects leverage the collaborative features of git/GitHub?

- Does collaboration in software development mirror, or differ from, collaborative practices in archaeological research more broadly?

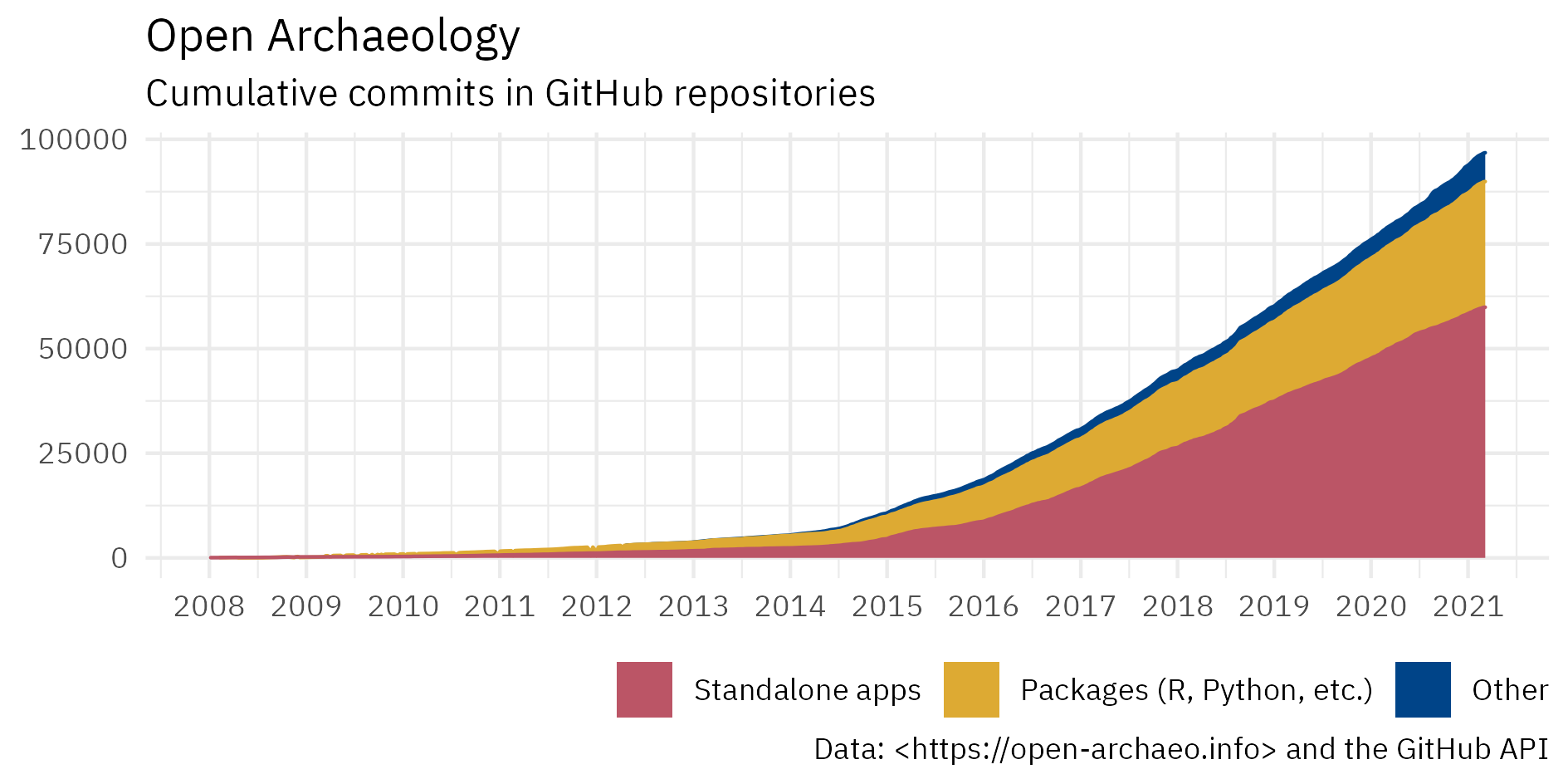

We find that collaborative open source software development in archaeology, measured both in the number of projects and discrete contributions tracked in git repositories, has seen a rapid and sustained increase beginning around 2015 (see figure). This growth is seen across a range of languages and categories of tools, but is strongest in standalone web apps and R packages. In terms of collaboration, our analysis shows an uneven use of git and GitHub’s extended features, beyond their basic usage as a version control system and repository host. The vast majority of repositories have 1–3 contributors, with only a few distinguished by an active and diverse developer base. Similarly, collaborative features such as GitHub “issues” are used in only a minority of repositories. However, a network analysis of repository contributors may point to some nascent communities of practice.

We highlight areas in which archaeologists are either pooling resources for common goals or working independently and in a redundant manner, factors that may contribute to either enthusiastic upkeep or abandonment of software development projects, how various means of communication and contribution are valued, and how GitHub is leveraged for either one-way or discursive means of engaging with relevant stakeholders. We consider these aspects of collaborative software development in relation to common structures, practices and challenges that bind archaeologists together as a distinct community, and draw comparisons with potentially conflicting underlying assumptions, attitudes and processes accounted for and encouraged by the infrastructures that archaeological software developers have come to rely upon. We demonstrate how archaeological software engineering is beginning to foster new kinds of collaborative commitments while also being rooted in established archaeological sociotechnical structures.

References

Baxter, Rob, N Chue Hong, Dirk Gorissen, James Hetherington, and Ilian Todorov. 2012. “The Research Software Engineer.” In Digital Research 2012, Oxford.

Schmidt, Sophie C, and Ben Marwick. 2020. “Tool-Driven Revolutions in Archaeological Science.” Journal of Computer Applications in Archaeology 3 (1): 18–32. https://doi.org/10.5334/jcaa.29.

Links

- Source repository (GitHub)